Randi Nygaard Lium ©

Since World War II, Norwegian tapestry art has blossomed into a lively and innovative art form. It has changed from the expressive medium of a few lonely artists to an independent discipline with numerous practitioners. Innovation, variety and luxuriance are key terms to characterize the weaving renaissance of recent decades. A strong tradition combined with international influences has encouraged growth and development.

In rough terms, the history of Norwegian tapestry art can be divided into five significant periods:

- Folk art tapestry weaving, 1650-1750

- The weaving renaissance, ca. 1900

- Monumental tapestry art, ca. 1950

- Tapestry art and the visual arts, 1960-1970s

- Tapestry art and the visual arts in late modernism and postmodernism, 1980-2002

Folk art tapestry weaving, 1650-1750

Norway’s oldest known tapestry is the Baldishol Tapestry, which was found in a church in the county of Hedemark in the late 19th century. This remarkable piece of work, believed to have been woven during the 12th century, is a unique relic of Norwegian tapestry history. Both the materials and the workmanship were of very high standard.

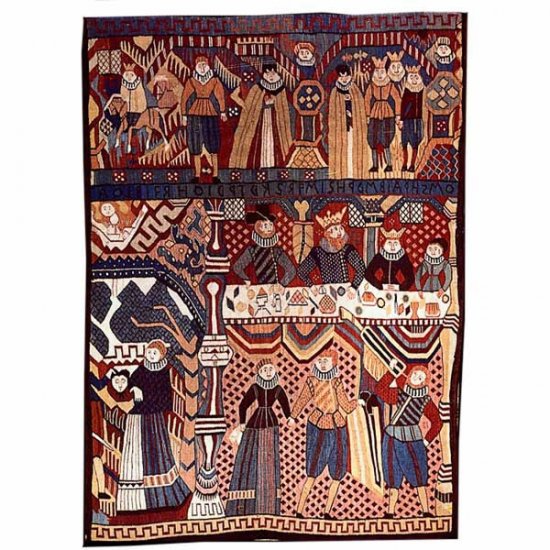

As a refined craft and form of expression, tapestry weaving first became established in Norway in the 17th century. During the baroque and the rococo in the 17th and 18th centuries, tapestry weaving blossomed as part of the folk tradition in Norway. Many beautiful and highly individual tapestries were woven using hand-spun and plant-dyed wool. These frequently illustrated religious themes, such as the five good and the five bad virgins, or Herod’s banquet. It was primarily young, unmarried women who wove tapestries. The centre for tapestry weaving at that time was the northern villages in the valleys around Gudbrandsdal. The weavers were generally the daughters of civil servants, who learnt their craft from their mothers.

The motifs they used, originally from taken from printed graphics were passed on as an inheritance from one generation to the next. These evolved steadily over time. Ornamentation was essential, and sometimes resulted in inscriptions becoming quite illegible. These tapestries were of a particularly abstract character. The techniques, quality and treatment of illustrative themes in these historic artifacts provided a background and a source of inspiration for the development of Norwegian tapestry weaving in the 20th century.

Chequered weaving. In the 18th century, many superb chequered-weave tapestries, with fine patterning and beautiful ornamentation, were woven in the valleys along Norway’s western coast.

The weaving renaissance, ca. 1900

Tapestry art received considerable interest in the late 19th and early 20th century. This was related to the general growth in interest in traditional handcrafts that was stimulated not least by the Art and Crafts movement in England. The Husflidsforening (Norwegian home crafts association) and the various museums of industrial art that were set up in Norway in the late 19th century showed particular interest in collecting older tapestries. The provision of training in traditional handcraft techniques was also regarded as an important task.

Gerhard Munthe and Frida Hansen. During Norway’s struggle for independence from Sweden in the years before 1905, the visual arts played a crucial part in creating symbols of identity. Tapestry art based on themes from Norwegian folktales and legends, and older Nordic mythology, became particularly significant. The painter Gerhard Munthe produced a series of aquarelles illustrating folktales, which were rendered into tapestries at the workshop for art weaving at the Nordenfjelds Museum of Industrial Art in the years 1897-1909.

During the same period, Frida Hansen (1863-1932) gained prominence as the Norway’s first great textile artist. She created designs that she herself then wove. Hansen was born and grew up in Stavanger, where she married a wealthy businessman whose firm went bankrupt during Norway’s economic difficulties around 1880. To make ends meet Frida Hansen opened an embroidery shop in Stavanger. In 1892 she moved to the capital, Christiania, where in the same year she founded the Workshop for National Tapestry Weaving, along with its own dye house.

Frida Hansen was highly prolific and oversaw a considerable production of tapestries, with many people employed to weave and dye the yarn. She was an innovator in Norwegian art at the turn of the century. In 1900 she contributed to the World Exhibition in Paris, where her work earned her a gold medal. This marked her international breakthrough, and she subsequently sold tapestries to a range of foreign museums.

Frida Hansen’s tapestries came to be regarded as among the best in Europe. She created a series of works in large-scale format on historical themes. Her orientation was international. She was an early exponent of the new Jugendstil, which became so popular around 1900.

Monumental tapestry art, Norsk Billedvev A/S ca. 1950

A fruitful collaboration between painters and eminent weavers formed the basis for a fresh resurgence of national tapestry art at the workshops of Norsk Billedvev A/S (Norwegian Tapestries Ltd.). This development mirrored that of the Atelier for Norsk Kunstveving (the Workshop for Norwegian Art Weaving) in Trondheim at the turn of the century. The contemporary political situation in the country also had parallels with that earlier period. National growth was important to the rebuilding of Norway after the war. And once again, tapestry weaving acquired central significance. Norsk Billedvev carried out a number of monumental public commissions, including works for the New City Hall in Oslo in 1950. At the same time, the baroque and renaissance tapestry art became the object of intense study by highly skilled craftspeople such as Else Halling and Sunniva Lønning.

The 1950s and 60s saw the creation of many fine tapestries. Several well-known painters were associated with the Norsk Billedvev workshop, among them Karen Holtsmark, Kåre Jonsborg and Håkon Stenstadvold. Karen Holtsmark created the design for a tapestry entitled Solens gang (The Way of the Sun), which in 1959 won a competition for a major decorative work to hang in the central hall of the Storting.

Hannah Ryggen, a poet in weaving. In the same period, Hannah Ryggen (1894-1970) also acquired prominence as another great innovator in Norwegian tapestry art beside Frida Hansen. Ryggen originally came from Malmö in Sweden, but in 1924 she settled in Ørlandet in the county of Trøndelag after marrying the Norwegian painter Hans Ryggen. In large-format tapestries woven from hand-spun and plant-dyed yarn, she developed her own personal and original form of expression. She was deeply engaged in social issues, and her tapestries became characterized by a powerfully expressive visual language that articulated the same attitudes and involvement that she showed in social debates.

Hannah Ryggen was intensely interested in literature. Due to the narrative pictorial content of her tapestries she has often been regarded as a poet in weaving. She also addressed personal questions in her works.

Hannah Ryggen is considered one of the foremost Norwegian tapestry artists of the 20th century. In 1964 she represented Norway at the Venice Biennial.

Synnøve Anker Aurdal (1908-2001) emerged on the Norwegian art scene in the late 1950s. Her artistic breakthrough came with the works she created for Håkons Hall in Bergen (1958-61), a public commission that she won together with Ludvik Eikaas and Sigrun Berg. The abstract, frieze-like tapestry in front of the royal seat in Håkons Hall anticipates later non-figurative tapestries, while at the same time containing clear historical references to older Norwegian tapestry art.

In 1971, the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs asked Synnøve Anker Aurdal to create a large-scale tapestry as a gift from Norway to Iceland on the opening of the latter’s national library. The result was Rommet og ordene (Space and Words) (1977).

Aurdal also represented Norway at the Venice Biennial in 1982. Whereas Hannah Ryggen created masterpieces of figurative, narrative tapestry, it was Synnøve Anker Aurdal who introduced and established the non-figurative image in Norwegian tapestry art.

Tapestry art and the visual arts, 1960s – 1970s. Material as message.

The material is the message. Materials have authentic force and constitute in themselves an expressive factor in an artwork. In the spirit of this basic doctrine, many freely conceived pieces of weaving were produced in the 1960s and 70s. The avant-garde in the field was associated with Eastern Europe, where Poland was the focal power. In that country textile art was respected as a fine art in its own right, on a level with painting, graphics and sculpture. Another important event in the 1960s was the establishment of the International Textiles Biennial in Lausanne in 1962, which was started on the initiative of the French painter and weaver Jean Lurcat.

In 1963 Britt Fuglevaag went to Poland for postgraduate studies, having completed her initial training at the National College of Art and Design in Oslo. There she found an attitude to weaving and its possibilities that was different from and freer than the one she was used to in Norway. She began to weave large, three-dimensional tapestries in durable materials such as hemp, jute and plastic, and had considerable success with this new, avant-garde expression. She took part in the Biennial at Lausanne in 1967 and 1971.

The 1970s – a colourful struggle. Whereas the 1960s had been characterized by the search for materials and experimentation, the decade that followed had other concerns on its agenda.

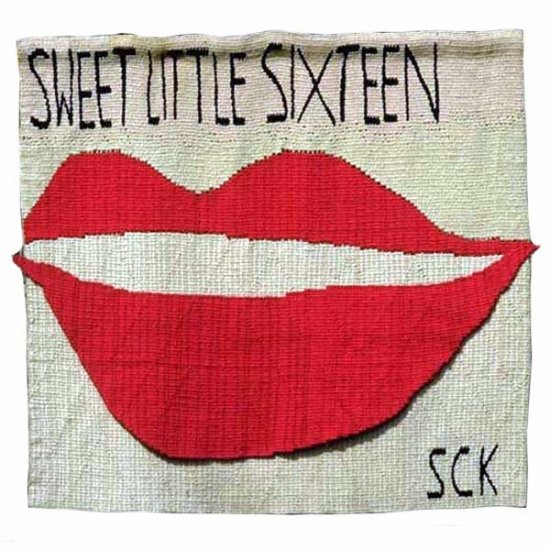

Artist activism and the struggle to elevate tapestry to an equal status with other visual arts were characteristic of the 1970s. The textile artists won their battle, and in 1977 the Norske Tekstilkunstnere (the Association of Norwegian Textile Artists) was founded, a new organization that enjoyed the same status as other professional interest groups within the Norske Billedkunstneres Fagorganisasjon (the Association of Norwegian Visual Artists). In the Association of Norwegian Textile Artists women were in the majority. Among the active artists in the 1970s were Kjell Mardon Gunvaldsen, Elisabeth Haarr, Else Marie Jakobsen, Sidsel Karlsen and Tove Pedersen.

Significant political events set the tone for the artistic work, among them the Vietnam War and the struggle against the EEC. Women’s rights were also a central concern. A generation of young women artists with feminist interests found their voice in the expressive medium of textiles. Many wove tapestries with clear political messages, relating both to broader political issues and to feminist themes. Tapestry art was also oriented towards new currents in visual arts, including pop art, minimalism and new figuration.

Tapestry art and the visual arts in late modernism and postmodernism, 1980-2002

In many ways the last 20 years have been an interesting and important period in the history of Norwegian tapestry art. The art form blossomed anew in the mid-1980s, when a number of interesting artists gained reputations for their classical tapestries, based on masterly technique and a superb sense of materials. Their designs were generally abstract, ornamental or minimalist in expression, or expressed a lyricism for nature. Several of the artists active in this period, among them Ellen Lenvik, Marianne Mannsåker and Ingunn Skogholt, had studied at art academies outside Norway.

As one of the few male practitioners of this medium, Jan Groth achieved an international reputation and has sold works to several foreign museums, including the Guggenheim Museum in New York. In the autumn of 2001 he had a large exhibition at the National Museum of Contemporary Art in Oslo.

Norwegian Tapestry enters a new millennium. In 2002 Sidsel Blystad demonstrated the effectiveness and continuity of tapestry art in monumental decorative commissions in Norway. She won the competition for a new work to be hung in the Storting. Sidsel Blystad’s work will replace Karen Holtsmark’s tapestry Solens gang (The Way of the Sun) of 1959, which is being removed due to wear and tear.

The new commission for the Storting will stand as a manifesto for the central role of tapestry in public art projects in Norway.